Those ‘Alien Megastructures’ Are Probably Just Dust

New data suggest a very natural explanation for what’s happening around the “most mysterious star in the universe.”

In 2015, The Atlantic first reported that astronomers had discovered some tantalizing information about a distant star in the Milky Way, located about 1,300 light-years from Earth in a swan-shaped constellation called Cygnus. The star itself, slightly bigger than our sun, seemed pretty ordinary as far as stars in the universe go. But every now and then, the light of the star appeared to dim and brighten.

This wasn’t the weird part. Astronomers look for faint dips in brightness in their search for exoplanets around other stars all the time. The dimming means that something is passing in front of a star and blocking some light from reaching Earth. Telescope observations have discovered thousands of exoplanets in this way.

The weird part about this star was the behavior of those light fluctuations. The flickering seemed almost random. Some dips in light lasted a few hours, while others lasted for days or weeks. The light dimmed by 1 percent at some times, a change that would typically suggest the presence of a Jupiter-sized exoplanet around the star. But at other times, the light would dim by more than 20 percent, a drop that suggested something much more massive was passing by.

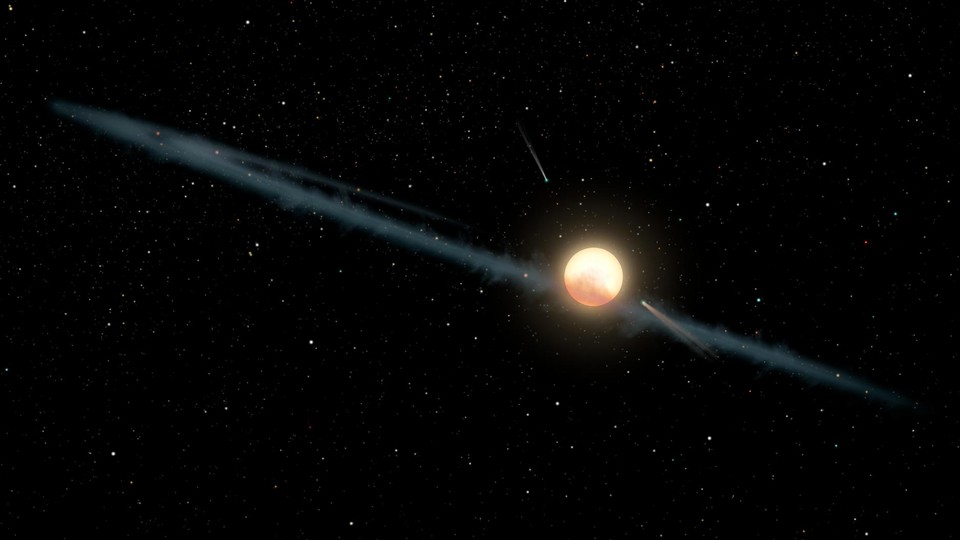

The star’s sporadic dimming stumped astronomers, who dubbed it “the most mysterious star in the universe.” They proposed several natural theories, like a transiting comet. When none seemed to fit the bill, they started considering something else. Could the object passing in front of this star, blocking out the light, be a swarm of alien megastructures built by an advanced civilization?

It was an exciting explanation, one that harkened back to a kind of technology imagined by the science-fiction writer Olaf Stapledon, and later popularized by the physicist Freeman Dyson, that would allow intelligent extraterrestrial life to harness the energy of their star.

It’s also probably the wrong one.

The mysterious flickering around the star in the swan constellation is likely caused by ordinary dust, according to an analysis of new data published Wednesday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Astronomers have found that the mystery dimming is much deeper at blue wavelengths than at red wavelengths, which means the object responsible for it is not opaque. The data suggest that the dimming is likely caused by a cloud of very small particles of cosmic dust, which measure less than one micron each, smaller than the size of a human red blood cell.

“If you imagine you have some light source and a planet—which is an opaque object—goes in front of it, it will block blue light just as much as it would the red light,” said Tabetha Boyajian, an astronomer at Louisiana State University who led the analysis. “What we’re seeing for this star is that the drop in the star’s brightness is much greater in the blue than it is in the red.”

If the dimming had occurred in all colors equally, megastructures would still be on the table. “The fact that the data came in the other way means that we now have no reason to think alien megastructures have anything to do with the dips of Tabby’s Star,” wrote Jason Wright, the Pennsylvania State University astronomer who first suggested the alien megastructure theory, in a blog post Wednesday. (Astronomers have nicknamed the star Tabby’s Star, after Boyajian.)

Searches for radio signals coming from the star have also turned up empty, providing another blow to the alien theory.

The strange flickering from Tabby’s Star was first detected by the Kepler Space Telescope, an exoplanet-hunting mission that started looking for changes in the brightness of stars in 2009. The mission produced an enormous amount of data. Boyajian made it public through a program called Planet Hunters and asked volunteers to comb through it, looking for patterns that would be difficult for fast-moving algorithms to spot. In 2011, citizen scientists flagged one star. Of the 150,000 stars Kepler had observed, this was the only one that exhibited this strange behavior.

After the news of Tabby’s Star was made public in 2015, other astronomers started digging into its past. They found another kind of dimming phenomenon, one that spanned years. In 2016, astronomers said their examination of old photographic plates from as early as 1890 revealed the star has been gradually decreasing in brightness for more than century. Later that year, astronomers revisited Kepler data and found that the star actually dimmed slightly every year by about 0.34 percent. Tabby’s Star kept getting weirder and weirder. None of the data fit any one explanation nicely, whether it was a swarm of comets or alien megastructures.

Cosmic dust started looking like one of the best culprits in October 2017. Astronomers analyzed the light from Tabby’s star over time and found more dimming in blue light than in red light—the same effect Boyajian measured during the real-time observations of the dips. Boyajian and other astronomers said Tabby’s Star was probably surrounded by clouds of circumstellar dust, grains that orbit around a star and are slightly bigger than interstellar dust. Circumstellar is just big enough to stick inside the star’s orbit, but too small to block light in all wavelengths.

The latest analysis comes from data collected between March 2016 and December 2017. Boyajian and her team observed the star with the Las Cumbres Observatory, an effort largely funded by a Kickstarter that raised more than $100,000. In May, the star started to dim. Boyajian tweeted about it, sending astronomers around the world into a frenzy as they raced to point other telescopes at Tabby’s star. It was the first time scientists had witnessed one of the star’s mysterious dips in real time. A second dip was recorded in June, a third in August, and a fourth in September. The dimming varied between 1 percent and 2.5 percent, and lasted between several days and several weeks.

While the latest observations seem to rule out the possibility of alien megastructures, they don’t completely solve the mystery of Tabby’s star. Boyajian and her team had expected to detect an excess of infrared light, created when starlight hits surrounding dust, but they saw none. “That was really surprising,” Boyajian said. “It’s kind of telling us, okay, this is not going to be easy.” There are several possible explanations, including that the dust may be too far from the star to become bright enough to glow in infrared.

Boyajian said more papers will be coming in the next few months on the rest of last year’s observations. “There’s still a possibility that we don’t really have a theory that’s correct yet,” she said. The cosmic-dust theory provides an answer to one of the questions posed by Tabby’s Star, but others remain.

Their answers may not even be something we would recognize if we saw it. As Wright and his colleague Kimberly Cartier wrote in an article last year, “Whatever is responsible may lie outside the realm of known astronomical phenomena.”